Every business that lends money, leases assets, or issues invoices is sitting on future cash.

The problem is timing.

That cash doesn’t arrive in a satisfying lump. It trickles in. Month by month. Invoice by invoice. Payment by payment. Meanwhile, the business still has wages to pay, suppliers to placate, and growth plans that refuse to wait politely.

Those future payments have value.

They’re just inconveniently slow about revealing it.

Securitisation exists to solve that problem.

Instead of waiting years for money to arrive, a business can reorganise those future payments so that investors provide funding upfront and are repaid as the cashflows come in. Everything else in a securitisation structure exists to make that simple trade acceptable to everyone involved.

Despite its reputation, securitisation isn’t complicated.

It’s a timing solution – with very good lawyers.

The Basic Idea

Mortgages generate monthly repayments.

Car loans pay down over time.

Trade receivables turn into cash when customers eventually decide that today feels like a paying day.

All of those future payments are valuable. The difficulty is that they arrive gradually, unevenly, and usually at exactly the wrong moment if you’re trying to run or grow a business.

Securitisation takes those future payments and uses them to raise money today.

Instead of waiting five years to be paid in full, a company can:

The company gets cash upfront.

Investors get exposure to defined cashflows.

Risk is shifted, reshaped and priced along the way.

That’s securitisation.

No mystery.

No alchemy.

Securitisation Isn’t Just Borrowing

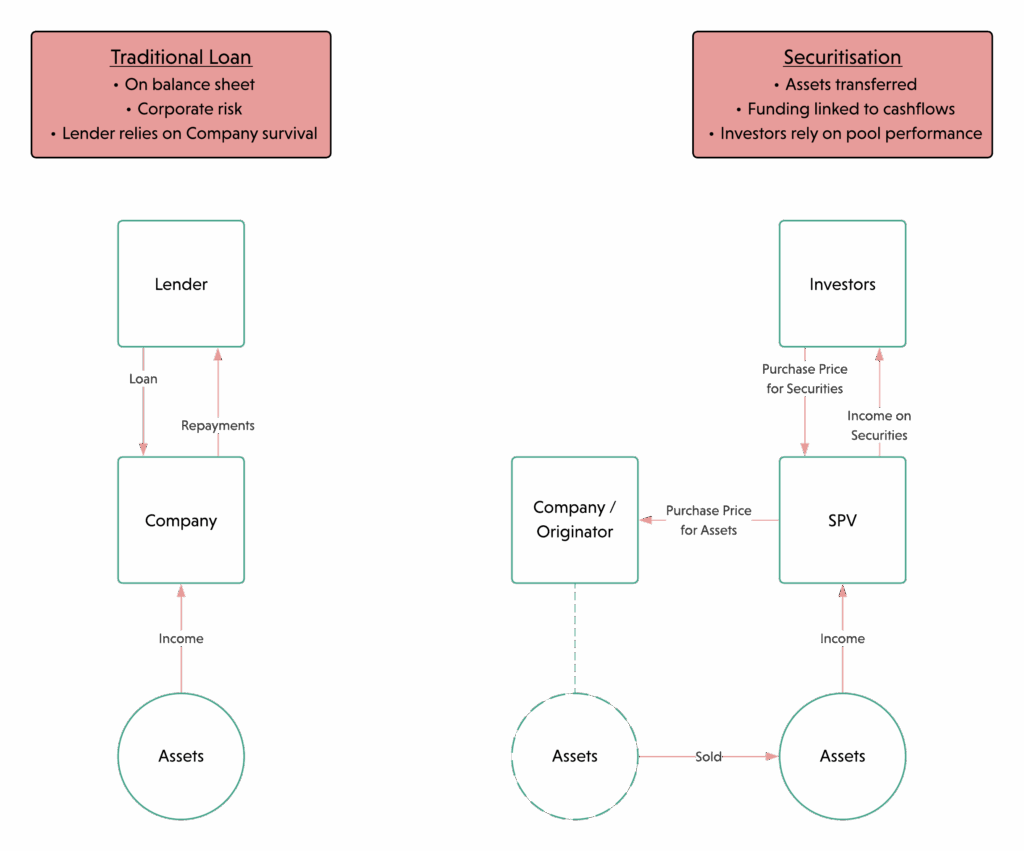

It’s tempting to think of securitisation as just another form of borrowing. Money comes in at the start. MoneIt’s tempting to think of securitisation as just another form of borrowing. Money comes in at the start. Money goes out later. Tick the box and job done.

That temptation should be resisted.

In a traditional loan:

In securitisation:

That’s why securitisation is described as off-balance-sheet funding – not because anything’s being hidden, but because the risk has genuinely moved.

The investors aren’t lending to the company.

They’re buying exposure to the cashflows.

That difference isn’t technical nit-picking. It’s the whole point.

Why Pooling Matters

If securitisation were about financing a single loan or a single invoice, nobody would bother.

One borrower defaults and the entire structure collapses. End of story.

Pooling changes everything.

By combining hundreds or thousands of similar assets:

That’s why securitisations gravitate towards:

One unpaid invoice is risky.

Ten thousand invoices behaving roughly as expected are boring.

And boring, in structured finance, is a feature.

Pooling isn’t about making things complicated.

It’s about making risk measurable – which is the only kind of risk markets will reliably finance.

The Role of the SPV (Briefly, for Now)

Rather than holding these pooled assets directly, securitisations almost always use a Special Purpose Vehicle – an SPV.

The SPV exists for one reason only: to sit between the originator and the investors.

And crucially, it’s designed to be boring.

No side projects. No ambition. No entrepreneurial flair. The SPV exists to do exactly what it says on the tin and nothing else. If the originator fails, the assets should keep performing inside the SPV without anyone panicking.

Securitisation works because the cashflows are separated from the company that created them. Everything else is decoration.

Who’s Involved?

At a high level, every securitisation has the same three essential characters.

The originator

The business that created the assets – the lender, lessor, or supplier issuing invoices.

The SPV (issuer)

The entity that buys the assets and issues the securities.

The investors

Institutions looking for predictable returns backed by defined cashflows – not a front-row seat to corporate drama.

Around them orbit servicers, trustees, banks, lawyers, accountants, and rating agencies. All important. All busy. But structurally, those three roles are the foundation. Everything else exists to keep the machine running smoothly.

A Concrete Example: Trade Receivables

Trade receivables securitisation is one of the clearest ways to see how this works in practice.

A company issues invoices to customers. Payment’s due in 30, 60, or 90 days. Cashflow is lumpy. Growth stalls. Anyone who’s waited for a large customer to pay will recognise the feeling immediately.

Instead of waiting, the company can:

The SPV uses those collections to repay its funders.

If structured properly, this isn’t a loan secured on receivables. It’s a genuine sale of future cashflows.

The company gets working capital.

Investors get diversified exposure.

Risk attaches to customer payment behaviour, not management optimism.

Scale the same logic up and you arrive at mortgages, car loans, consumer credit, and beyond.

What Securitisation Isn’t

Before going any further, a few myths need clearing up.

Securitisation isn’t:

What it actually does is:

When securitisations fail, they fail for reasons that are rarely mysterious:

The structure itself is neutral. It reflects the quality of what goes into it – not the quality of the sales pitch.

Why Securitisation Exists at All

If banks could lend infinitely, cheaply, and without constraint, securitisation wouldn’t exist.

They can’t.

Capital rules, funding costs, and regulatory limits mean balance sheets fill up. Securitisation allows lenders to:

At the same time, investors – pension funds, insurers, asset managers – want exposure to predictable cashflows without full corporate exposure.

Securitisation sits between those needs.

It isn’t unusual.

It’s plumbing.

The Last Word

If you remember one thing, remember this:

Securitisation is the sale of cashflows, not a loan to a company.

Everything else – SPVs, tranches, credit enhancement, ratings, documentation – exists to support that single idea.

And once that foundation is clear, the next question becomes unavoidable:

what gets securitised – and why do some assets behave far better than others?

That’s where things get interesting.

This article is part of a series examining how securitisation works in practice – from the assets involved, to the structures used, and how risk is allocated. Each article is written to stand on its own, while contributing to a broader explanation of securitisation and its role in modern finance.

Stay updated with the latest insights and articles delivered to your inbox weekly.

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest insights and expert advice

on funding structures.